Stories in Progress

The King of the World

As a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, Aharon Andrikian defied all odds. As a successful cobbler in Massachusetts, he embodied the American Dream. And as an eventual insane asylum resident—anonymous, homeless, belonging nowhere and to no one—he personified Other and the fear we feel in its presence.

Aharon’s is an epic story, spanning over 10,000 miles and countless tragedies. He was born and raised at the epicenter of Turkey’s current earthquake zone, which was then the epicenter of genocide. With his entire family lost to slaughter, he escaped to Russia, traveled across all of Siberia, and somehow made it onboard a ship sailing from Japan to Seattle. Upon achieving stability in the States, he suffered a breakdown, abandoned everything yet again, and traveled the West as a self-described messiah. He was beaten, incarcerated, driven from town to town, forced to live at the edges of society. Yet, all the while, he remained buoyant, hopeful, and eventually ebullient in his belief that he had been reborn as the King of the World.

The Long Way: A Memoir

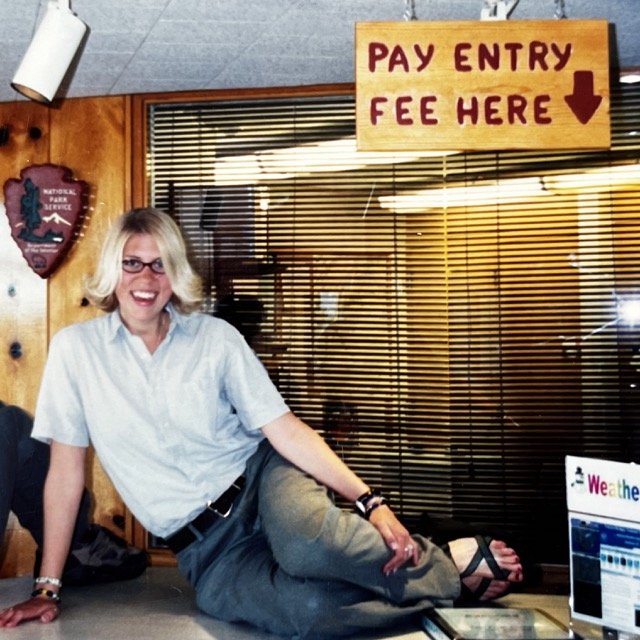

In my early twenties, while enduring the ramifications of my rapist’s poor social skills, I fled to the most conservative state in the nation to work some shit out. By “work some shit out,” I mean blithely sleeping with dangerous men, using my body to get my way, drinking to blackout on the regular, and myriad other explorations of the negative space of power, me confusing its emptiness for form.

The Mormon theocracy that is Utah does not condone such behaviors. Neither did my Catholic upbringing. The patriarchy, in general, frowned upon the coping mechanisms I crafted to survive within its embrace.

But the landscape, an entity ever beyond culture and gendered experience, saved me. With an opacity born of wildness, it mirrored exactly what I needed to see in myself.

My 125,000-word memoir, The Long Way, is my road map to redemption. It is the radically honest story of the holy trifecta of female pain and shame—rape, abuse, abortion—and the culture that generates these all-too common feminine texts. It is the story, too, of discovering the wilderness—the desert—as a place of refuge and solace.

Mike Miksche

My great-uncle was a wounded war hero and a celebrated commercial artist. He socialized with Andy Warhol and performed for Dr. Alfred Kinsey. He was, perhaps, both bisexual and bipolar, neither designation being acceptable—or even speakable—at the time. He was a major figure in New York’s nascent underground leather scene of the ‘50s, and he was commissioned by Sports Illustrated to generate artwork commemorating the 1956 Olympics. He was one of the first Marlboro Men. Across the poles of human experience, he achieved, he explored, and he suffered. Whether his untimely death was an accident or suicide, I will never know. All that I am left with are fragments of genius and pain.

The poet Robert Lowelll wrote of “seeing too much and feeling it with one skin-layer missing.” I believe Mike Miksche experienced the world in this way. He felt everything intensely, whether it be love or pain, curiosity or revulsion. And that made his life all the more remarkable. He felt his wounds acutely, and yet he did not sink into collapse; instead, he rose from it, time after time, open to beauty and cruelty in equal measure.